expressivism & classicism

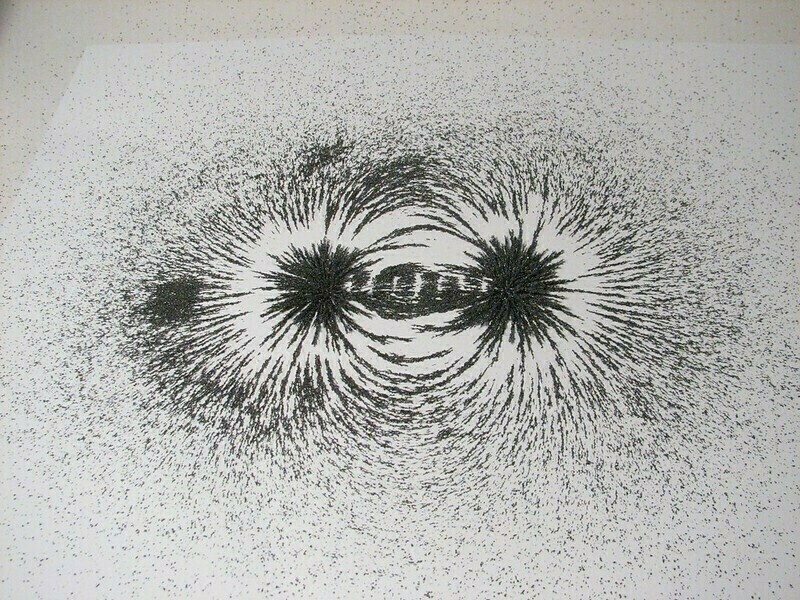

#The great works of European art music exist in an aesthetic field defined by the dipole of classicism and expressivism, the two generative sensibilities that drive (or drove) developments in musical style between about 1700 and 1950. By “dipole” I am not picturing a Venn diagram but something more like a magnet:

As in the magnetic field, classicism and expressivism are dialectical and interpenetrating, not antithetical and opposing. There is no “pure” specimen of either. No one work, or composer, ever exemplifies one sensibility to the total exclusion of the other. In one period a work may be predominantly classicist despite its composer utilizing musical language and form that were originally developed from expressivist impulses. (Note: I use these two terms here in largely ahistorical ways — small-c and small-e, not the capitalized historical movements Classicism and Expressivism — for lack of better terms occurring to me at the moment.)

The mark of classicism is the aspiration to balance and perfection in musical presentation. The classical sensibility yields the sort of work about which one thinks: “There was not a single note out of place” — even if, as the Emperor is supposed to have told Mozart, there may have been “too many notes.” Stereotypically, Western music loves four-bar phrases, clean chord progressions with well-prepared resolutions, standard accompaniment figures and phrases (the Alberti bass being the most famous), and the like: these are hallmarks of the classical. There is a self-conscious inhabiting of traditional forms, even as they may be innovated or subverted in various ways. To be sure, there may be musical surprises, but they do not feel experimental. To the listener there is little or no sense of struggle in the act of composition, no matter how dramatic the music itself may be. To the performer the chief difficulty is making the music seem effortless, regardless of the technical challenge it may pose. The overriding impression in the greatest of these works is of exquisite craftsmanship, occasionally of an almost unearthly or inhuman perfection.

The mark of expressivism is the aspiration to communicate the hitherto incommunicable, to somehow reach across the gulf between composer, performer(s), and audience. (Note the asymmetry between the two core aspirations.) The expressive sensibility yields the sort of work about which one thinks: “That was so powerful!” — even if, in places, it seemed overwrought or difficult to follow. (Bertrand Russell’s remark about Wagner’s opera is apposite: “marvelous moments, and dreadful quarters of an hour.") Traditional forms and stereotyped devices are used, but not loved; they are the composer’s vehicle, not his or her habitation. Every aspect of the music is, if not actually experimental, a potential site for experimentation; there are not so much musical “surprises” as a more or less steady experience of “surprise.” The listener is expected to not just hear but feel the sense of personal exertion that has gone into the composition; even the less dramatic moments reveal the struggle for expression by temporarily concealing it. To the performer the chief difficulty is summoning the emotional vigor to make the music seem sufficiently effortful. The overriding impression in the greatest of these works is of overwhelming genius, that the composer has somehow expressed the previously inexpressible.

The greatest of classicists is, of course, Mozart. There is nobody to match him — except perhaps Schubert, who stands after him but in the same rank. The second rank of classicists includes Mendelssohn, Chopin, Fauré, Tchaikovsky (yes, a classicist by temperament, except perhaps revealing his expressivist side in the Sixth Symphony!), Rachmaninoff, and the late Stravinsky (there’s something about those Francophile Russians). I am unsure whether to say Haydn is a classicist or an expressivist at heart; probably a classicist, albeit one who was toying with expressivism before it had come to full flower. Richard Strauss had the fullness of classicism within him — especially present, perhaps, in his Eine Alpensinfonie, in his Violin Sonata, and in some passages of the early tone poems. Mahler, too, wrote some marvelous classical passages, though mostly integrated into overall expressivist works — especially the waltz movements in his earlier symphonies; in his later period, the Sixth and Eighth Symphonies are remarkably classicist works despite the force of their expression.

The greatest of expressivists, who ushered this sensibility into maturity after Haydn had disclosed a new measure of its potential, is Beethoven. In his earliest works, one can hear him toying brilliantly (if sometimes unimpressively) with the classicism of his teachers, at times sounding impatient to get on to writing in his own way. His Third Symphony is still the touchstone expressivist (and Romantic) work, often imitated but never bettered, with its astonishing self-confidence, its total mastery of and almost equally total disregard for musical convention. More subtle in this regard, but no less masterful, are his late string quartets, especially Opp. 130 and 131. (But in the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies especially Beethoven showed that his embrace of expressivism did not indicate a total repudiation of classicism.) Wagner undoubtedly aspired to be, and maybe imagined himself to be, the greatest of expressivists, but he did not understand its hidden and tragic secret: that it depends irreducibly on the dialectical tension with the classicist pole for its power. Among Beethoven’s successors, the greatest expressivist accomplishments are those of Schumann (in the solo piano works), Mahler (in the Second and Ninth Symphonies), and Strauss (Ein Heldenleben), though they also at times exhibit the tragic tendency of expressivism to cut loose from classicism and thus lose itself. Also deserving mention are the French luminaries of expressivism, Debussy and Ravel. The early Schoenberg (cf. Verklärte Nacht and the first string quartet) had the promise of greatness, but his turn to anti-tonality was his undoing. Dmitri Shostakovich, long after much of European music had followed Schoenberg down his disastrous path, continued cultivating the genius of expressivism, as did his Soviet colleague Sergei Prokofiev.

In the middle zone of the dipole, offering remarkable and singular syntheses of these two sensibilities, stand J. S. Bach and Brahms. Perhaps less brilliant than those two, but great nevertheless, is Anton Bruckner, who offers his great expressiveness with remarkable musical economy and in a (yet more remarkable) spirit of humility. And the Vier letzte Lieder of Strauss dwell in the same extraordinary territory.

Next I need to read Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy — whose title, I just learned, originally continued … Out of the Spirit of Music — to see how closely my intuition here maps to his famous juxtaposition of Apollo and Dionysos.